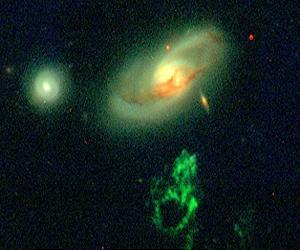

The green Voorwerp in the foreground remains illuminated by light emitted up to 70,000 years ago by a quasar in the center of the background galaxy, which has since died out. (Photo: WIYN/William Keel/Anna Manning) |

Two years later, a team led by Yale University researchers has discovered that the unique object represents a snapshot in time that reveals surprising clues about the life cycle of black holes.

In a new study, the team has confirmed that the unusual object, known as Hanny's Voorwerp (Hanny's "object" in Dutch), is a large cloud of glowing gas illuminated by the light from a quasar-an extremely energetic galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its center.

The twist, described online in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, is that the quasar lighting up the gas has since burned out almost entirely, even though the light it emitted in the past continues to travel through space, illuminating the gas cloud and producing a sort of "light echo" of the dead quasar.

"This system really is like the Rosetta Stone of quasars," said Yale astronomer Kevin Schawinski, a co-founder of Galaxy Zoo and lead author of the study. "The amazing thing is that if it wasn't for the Voorwerp being illuminated nearby, the galaxy never would have piqued anyone's interest."

The team calculated that the light from the dead quasar, which is the nearest known galaxy to have hosted a quasar, took up to 70,000 years to travel through space and illuminate the Voorwerp-meaning the quasar must have shut down sometime within the past 70,000 years.

Until now, it was assumed that supermassive black holes took millions of years to die down after reaching their peak energy output.

However, the Voorwerp suggests that the supermassive black holes that fuel quasars shut down much more quickly than previously thought.

"This has huge implications for our understanding of how galaxies and black holes co-evolve," Schawinski said.

"The time scale on which quasars shut down their prodigious energy output is almost entirely unknown," said Meg Urry, director of the Yale Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics and a co-author of the paper.

"That's why the Voorwerp is such an intriguing-and potentially critical-case study for understanding the end of black hole growth in quasars."

Although the galaxy no longer shines brightly in X-ray light as a quasar, it is still radiating at radio wavelengths. Whether this radio jet played a role in shutting down the central black hole is just one of several possibilities Schawinski and the team will investigate next.

"We've solved the mystery of the Voorwerp," he said. "But this discovery has raised a whole bunch of new questions."

Other authors of the paper include Shanil Virani, Priyamvada Natarajan, Paolo Coppi (all of Yale University); Daniel Evans (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Elon University); William Keel and Anna Manning (University of Alabama and Kitt Peak National Observatory); Chris Lintott (University of Oxford and Adler Planetarium); Sugata Kaviraj (University of Oxford and Imperial College London); Steven Bamford (University of Nottingham); Gyula Jozsa (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy and Argelander-Institut fur Astronomie); Michael Garrett (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Leiden Observatory and Swinburne University of Technology); Hanny van Arkel (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy); Pamela Gay (Southern Illinois University Edwardsville); and Lucy Fortson (University of Minnesota). Citation: Kevin Schawinski et al 2010 ApJ 724 L30 DOI: 10.1088/2041-8205/724/1/L30

spacedaily.com