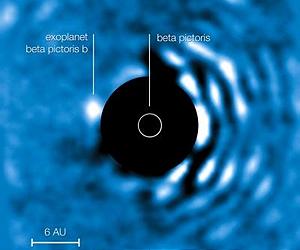

Using new optics technology developed at the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, an international team of astronomers has obtained images of a planet on a much closer orbit around its parent star than any other extrasolar planet previously found.The discovery, published online in Astrophysical Journal Letters, is a result of an international collaboration among the Steward Observatory, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, the European Southern Observatory, Leiden University in the Netherlands and Germany's Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy.

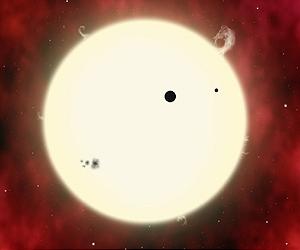

Installed on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, or VLT, atop Paranal Mountain in Chile, the new technology enabled an international team of astronomers to confirm the existence and orbital movement of Beta Pictoris b, a planet about seven to 10 times the mass of Jupiter, around its parent star, Beta Pictoris, 63 light years away.

At the core of the system is a small piece of glass with a highly complex pattern inscribed into its surface. Called an Apodizing Phase Plate, or APP, the device blocks out the starlight in a very defined way, allowing planets to show up in the image whose signals were previously drowned out by the star's glare.

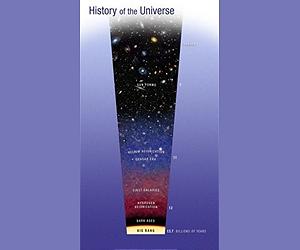

"This technique opens new doors in planet discovery," said Phil Hinz, director of the UA's Center for Astronomical Adaptive Optics at Steward Observatory. "Until now, we only were able to look at the outer planets in a solar system, in the range of Neptune's orbit and beyond. Now we can see planets on orbits much closer to their parent star."

In other words, if alien astronomers in another solar system were studying our solar system using the technology previously available for direct imaging detection, all they would see would be Uranus and Neptune. The inner planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars and Saturn, simply wouldn't show up in their telescope images.

To put the power of the new optics system in perspective: Neptune's mean distance from the sun is about 2.8 billion million miles, or 30 Astronomical Units, or AUs. One AU is defined as the mean distance between the sun and the Earth.

The newly imaged planet, Beta Pictoris b, orbits its star at about seven AUs, a distance where things get especially interesting, according to Hinz, "because that's where we believe the bulk of the planetary mass to be in most solar systems. Between five and 10 AUs."

While planet hunters have used a variety of indirect methods to detect the "footprints" of extrasolar planets - planets outside our solar system - for example the slight gravitational wobble an orbiting planet induces in its parent star, very few of them have been directly observed.

According to Hinz, the growing zoo of extrasolar planets discovered to date - mostly super-massive gas giants on wide orbits - represents a biased sample because their size and distance to their parent star makes them easier to detect.

"You could say we started out by looking at oddball solar systems out there. The technique we developed allows us to search for lower-mass gas giants about the size of Jupiter, which are more representative of what is out there."

He added: "For the first time, we can search around bright, nearby stars such as Alpha Centauri, to see if they have gas giants."

The breakthrough, which may allow observers to even block out starlight completely with further refinements, was made possible through highly complex mathematical modeling.

"Basically, we are canceling out the starlight halo that otherwise would drown out the light signal of the planet," said Johanan (John) Codona, a senior research scientist at the UA's Steward Observatory who developed the theory behind the technique, which he calls phase-apodization coronagraphy.

"If you're trying to find something that is thousands or a million times fainter than the star, dealing with the halo is a big challenge."

To detect the faint light signals from extrasolar planets, astronomers rely on coronagraphs to block out the bright disk of a star, much like the moon shielding the sun during an eclipse, allowing fainter, nearby objects to show up.

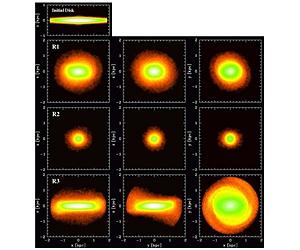

Using his own unconventional mathematical approach, Codona found a complex pattern of wavefront ripples, which, if present in the starlight entering the telescope, would cause the halo part to cancel out but leave the star image itself intact.

The Steward Observatory team used a machined piece of infrared optical glass about the size and shape of a cough drop to introduce the ripples. Placed in the optical path of the telescope, the APP device steals a small portion of the starlight and diffracts it into the star's halo, canceling it out.

"It's a similar effect to what you would see if you were diving in the ocean and looked at the sun from below the surface," explained Sascha Quanz from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology's Institute for Astonomy, the lead author of the study.

"The waves on the surface bend the light rays and cause the sky and clouds to appear quite different. Our optic works in a similar way."

In order to block out glare from a star, conventional coronagraphs have to be precisely lined up and are highly susceptible to disturbance. A soft night breeze vibrating the telescope might be all it takes to ruin the image. The APP, on the other hand, requires no aiming and works equally well on any stars or locations in the image.

"Our system doesn't care about those kinds of disturbances," Codona said. "It makes observing dramatically easier and much more efficient."

In the development of APP, Codona was joined by Matt Kenworthy (now at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands). Hinz, who is a member of the instrument upgrade team for the VLT, played a key role in the technique's implementation on the 6.5 Meter Telescope on Mount Hopkins in Southeastern Arizona.

Former UA astronomy professor Michael Meyer, now at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, where he led the group implementing the technology on the VLT, pointed out that APP is likely to advance areas of research in addition to the hunt for extrasolar planets.

"It will be exciting to see how astronomers will use the new technology on the VLT, since it lends itself to other faint structures around young stars and quasars, too."

spacedaily.com